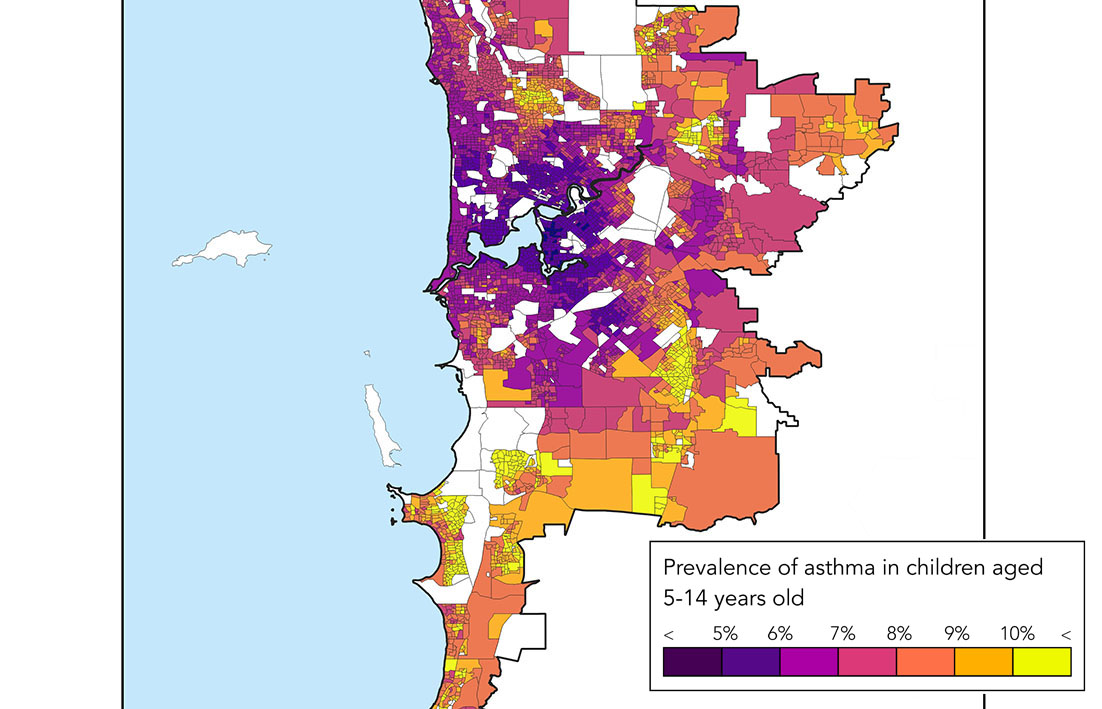

CHILDREN in outer suburbs like Midland, Butler and Girrawheen are twice as likely to have asthma than inner city suburbs, according to a new study.

The study, from a team of researchers from the Telethon Kids Institute, was released on March 12 and used data from the 2021 census to compare Australia’s four biggest capital cities to help map patterns of chronic disease.

Lead researcher and geospatial modelling expert associate professor Ewan Cameron said children aged between five to 14 years old, who live in the lower socio-economic suburbs of capital cities are twice as likely to have asthma compared to those from more affluent inner-city suburbs.

“Going in, we thought the inner city might have the most childhood asthma because of heavy traffic flow and air pollution but instead, the pattern we see is one of increasing asthma risk towards the outer areas of cities.” he said.

“The (outer) suburbs, with 12 per cent prevalence, had twice the rate of childhood asthma as the inner city (6 per cent).

“For Perth and Sydney, for example, when you look at the maps you immediately see it’s much lower in the more advantaged inner, northern and beach suburbs compared to suburbs that are more inland,” he said.

“We know from earlier studies, including the Raine study in Western Australia, that the risk of developing asthma is strongly shaped by socio-economic factors.

“These factors include higher rates of chronic family stress and poor housing quality, including dampness and poorly ventilated gas stoves, as well as dietary and obesity factors.”

Dr Cameron said climatic factors also play a major role in the likelihood of asthma developing in children, particularly in areas that experience large differences between day-time maximum and night-time minimum temperatures.

However, the research found some lower socio-economic suburbs in Perth, such as Hamilton Hill and Spearwood, had a lower asthma risk compared with Midland due to their coastal climate.

“We do find there’s a contribution from environment – places that experience large daily temperature variations tend to have higher risk of asthma. More extreme weather can be a factor in triggering asthma,” Dr Cameron said.

The findings highlighted the challenges faced by government and health authorities tasked with fighting Australia’s childhood asthma epidemic, Dr Cameron said.

“By revealing where asthma risk is highest at a fine level of precision – down to neighbourhood block size – we can identify the local government areas that need the most support,” he said.

“This means we can target interventions and policies to help those most at need and have the greatest impact.”