WA Historical Society members met recently at the Fremantle Port Authority to learn about the construction of the port, and to pay homage to the man who instigated the deepening of the inner-port to its present size, CY O’Connor and, of course, the Kalgoorlie Pipeline.

Under O’Connor’s towering statue Port Authority guides explained the difficulties and controversies of blasting one million cubic metres of sandstone that needed to be dredged away to complete the deepening.

It was achieved against much criticism, which, unfortunately, became a common theme for O’Connor’s great works.

He proved the doubters wrong, and the port received the first large liner in 1900.

Then-premier Sir John Forrest appointed O’Connor commissioner of railways and he became responsible for many of the country railway tracks still in use today.

Manning Clark, in his magisterial History of Australia, refers to the enlargers of life, those who propose and achieve great things against determined opposition – and O’Connor, according to Clark, was one such – a man of prodigious energy, ideas, and talent, yet regrettably possessed with demonic self-doubt.

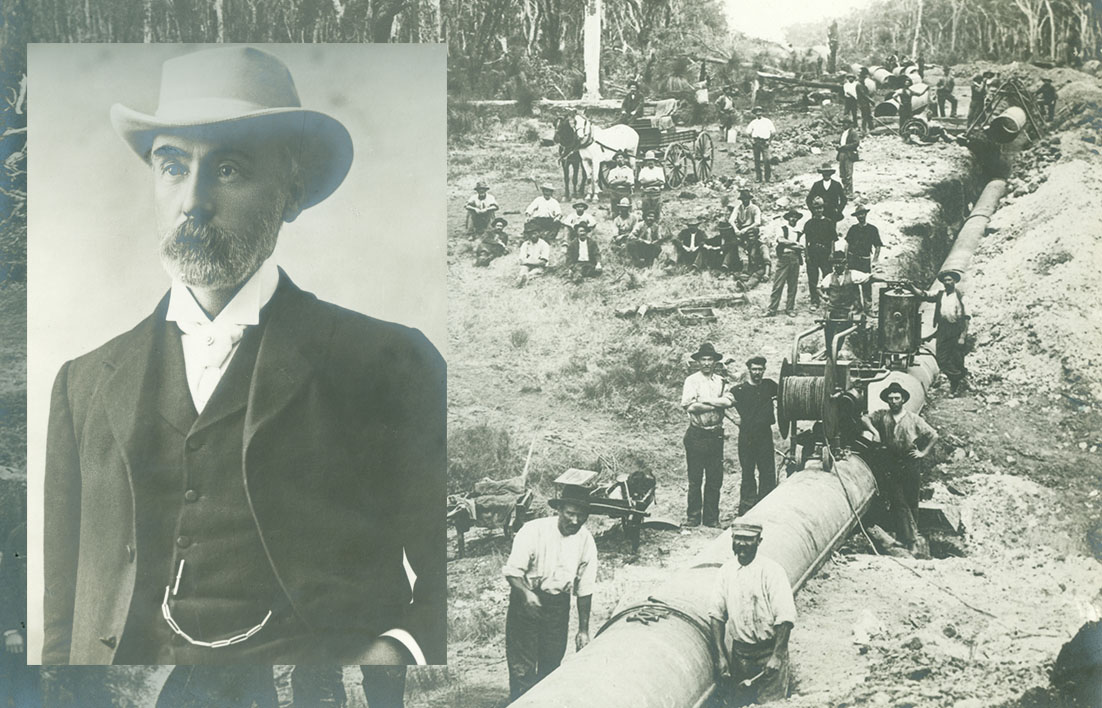

Sensitive to criticism, he nonetheless presented a seemingly outrageous plan to build a 600km pipeline from Mundaring to Kalgoorlie to service the booming Kalgoorlie region. With the urgent need for fresh water supplies following the 1890s gold rush, water was not only scarce, it was often polluted, hence fresh water was vital for the growth of gold mining and the agricultural expansion that was to come later along the life-giving pipeline.

Plans for the laying of 60,000 pipes and the necessary eight pump stations, took three years; all meticulously laid out by O’Connor and his team.

During this time, he received undiminished howls of protest from all sides of the community – the constrainers as labelled by Manning Clark; those who mock any great plan.

The state newspapers were particularly belligerent; The Sunday Times labelling the scheme sheer madness, even becoming personal, calling him ‘batty’. Similar sentiments came from members of state Parliament and much of the public, but he was undeterred, and the project began after an appropriation bill tabled by Forrest passed parliament in 1900. The pipeline was completed two years later.

It is remarkable that some 300km of the original pipes are still in situ and working, more than 120 years later.

New pipes are now replacing damaged ones, other links are being buried against possible future external damage. The burying of some of the pipes is hotly contested, with protest groups claiming it will destroy the visual heritage of the line; others point out that tourism plays an important part of the pipeline with many walking and bicycle trails, and vehicle sections, accessible and much-used by interested tourists.

Criticism became so hostile against O’Connor that it affected his nerves and health badly. So much so, before the completion of his mammoth project he rode out one morning into the sea at Robb Jetty and shot himself with a revolver.

The pipeline opened successfully less than a year later.

Charles Yelverton O’Connor rests peacefully at Fremantle cemetery; a beautiful memorial that stands testament to one of Western Australia’s greatest, if not most maligned, sons.